Hortense Powdermaker knew herself to be an anthropologist. Her study of the film industry during her time provides a comprehensive image — capturing the zeitgeist of the Golden Age by providing details and examples of the people and places. According to Wikipedia (for which I suspend my disbelief), her Hollywood: the Dream Factory is “the only serious anthropological study of Hollywood.” This leads me to believe that either the culture was so deeply ingrained in the system, that these archetypal situations were so prevalent — or that Vincente Minnelli read Powdermaker’s book before making The Bad and the Beautiful. The funny thing about it is that the majority of the film occurs in flashbacks, but these common experiences must have imprinted so heavily/were so pervasive over the first half of the 20th century that they were impossible to ignore.

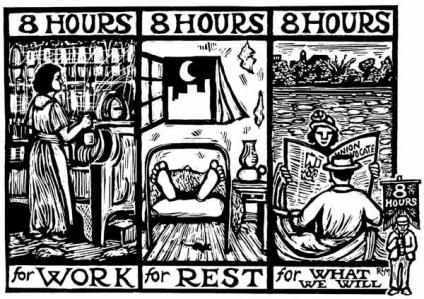

Powdermaker speaks about the dualism between business and art in the film industry. This reminded me of a concept we discussed in my other senior seminar — that of bread and roses. The term rose from those fighting for fair labor, namely Rose Schneiderman (1882 – 1972). She coined the term while referring to the need for a living wage (bread) and simultaneously proud living (roses).

Bread for some is business — the Mr. Rough-and-Ready that Powdermaker posits is similar to Harry Pebbel. He cares not as much for art as long as profits come back to him. He says, “I’ve told you a hundred times. I don’t want to win awards. Give me pictures that end with a kiss and black ink on the books.” And bread for others is their art — the money they make matters less as long as they are personally satisfied with their final product. While Jonathan Shields is at one point this way. This is after a life on the business side. As Powdermaker says, “but it is interesting that they [producers] are often not content to be businessmen controlling artists. They want to be artists, too. Because they have so little understanding of the creative role it is easy for them to think they are playing it.” (112) But he becomes swept up in the Hollywood world — the glamour he knew as a child becomes a miserable existence because of the people he hurts.

Shields has his fall from grace three times, each ending with him forever scarring a person he once cared for, and digging himself deeper into a hole. Ironically, his failures only make the successes of those he hurt greater.

Both Powdermaker and Minnelli show the folly of man (specifically) — the former in a clinical fashion and the latter to evoke emotional response in the viewer (I could write a whole post about the directorial God that Minnelli writes about and also plays). Powdermaker’s reasoning proved ultimately compelling to me in the context of the film:

“Movie production does give many men the opportunity to live out their deep personality needs for gambling and power, and in so doing to make great fortunes. Yet they can never be satisfied because their needs are insatiable. No matter how large the profits, how many Oscars, they must go on constantly striving to prove to themselves that they are supermen. A pause in the activity — and questioning voices might be heard; the only way to silence these voices is through further activity.” (290)

Even after Shields goes bankrupt, he cannot live without asking those who he had success with to take one final chance on him. The director Mike Nichols once said “every scene is either a fight, seduction, or negotiation.” The trio is done fighting with Shields, but the activity continues. Superman must seduce and negotiate with them.

Leave a comment