A bit about the history of gratuity.

Although the precise origin is not agreed upon, tipping began as an aristocratic habit in Europe sometime around the 1600’s. Some historical accounts of tipping provide accounts of detailing how European aristocrats would hire bodyguards for protection and would give extra coins along the way to guarantee their continued safety, while others recall the English practice of ‘giving vails’, meaning to give a small consideration for servants who performed above average.

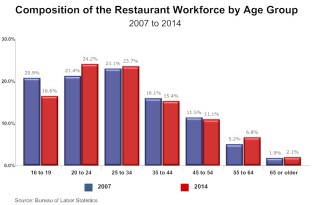

Over the last eight years, a steady departure of youth labor from the restaurant workforce has shown a predictable increase in the 20-24 demographic, but a shocking increase in people over 55. What might be contributing to this rise?

Tipping found a foothold in eighteenth-century America around the end of Civil War, codified by a section of the American elite who found their way to Europe. However, the practice invited intense resistance from many Americans who saw it as an archaic institution heralding back to the times of princes and paupers. Tipping encourages service laborers to act servile, to acquiesce to the most egregious request for the sake of salary.

Back then, all wages were paid by employers and there was actually a huge anti-tipping response in America because of the practice’s connection to archaic European aristocratic ideologies. It wasn’t until the Prohibition that tipping gained traction amongst business owners reeling from the loss of alcohol sales who found tipping let them save money on labor costs.

The neo-liberalism of the 1970’s cemented labor practices like tipping into the mainstream labor vocabulary because as Andrew Ross reminds us in his book, The Humane Workplace, mass deregulation stripped away many of the “supporting structures within the organization…leaving individuals to assume obligations that the company, or the state, had previously shouldered.” (Ross, 253).

American William Scott expresses this egalitarian response to tipping well in his book The Itching Palm, 1916:

“In the American democracy to be servile is incompatible with citizenship. Every tip given in the United States is a blow at our experiment in democracy. The custom announces to the world…that we do not believe practically that all are created equal. […] If any form of service is menial, democracy is a failure. Those Americans who dislike self-respect in servants are undesirable citizens; they belong in an aristocracy.”

I’ve worked as a server for a little under two years now and I worked in kitchens and sandwich lines for the two years before that. I mention these earlier jobs because they work well to provide a comparison example of the benefits and drawbacks of Fordist and post-Fordist labor. I worked untipped first for Jimmy Johns, making seventy-five cents over minimum wage (which four years ago in Colorado meant $7.50) I worked on the sandwich line, which meant you’d either be taking an order, making an order (both of which are very streamlined, mindless processes designed to be taught in a day) or cleaning the store. “If you’ve got time to lean, you’ve got time to clean.”

I was hesitant to include this graphic because I was afraid it would encourage the very practice that I would like to see abolished, but I think that this really illustrates just how many kinds of jobs don’t have fair wage practices and resort to using tips as a way to manage lower labor costs.

I hated working there. My labor was menial, customers were often rude or impatient, and the meager minimum wage plus seventy-five cents paychecks I would get every two weeks did not feel commensurate to the sacrifice I felt I was making every day by working at the damn place. So I found a job in a kitchen at a dine-in restaurant. I started off at $11.50 and it was never hard to find hours to work. The money made it worth it, but the work did too. Instead of feeling like an underpaid cog in an ultimately pointless assembly line, I was making and plating food to be served to customers. I was becoming a skilled laborer (I started off as a dishwasher and fry cook, but ended up doing food prep before we opened and making salads and appetizers).

However, working in the kitchen is hard. You’re either the first one (8:00 am) in or the last one out ( as late as 1:00 am on Friday and Saturday with the night shift starting at 4:00 pm) — unless you’re working a double and then you’re both. Servers, on the other hand, started at 10:30, 11:00, and noon and were out well before the kitchen staff. And, depending on how good business was, servers would often make relatively equivalent pay working twenty-five or thirty hours to my forty. These aspects of serving, ultimately, are what made me want to work as one, and they are the main reasons that I have continued to do so over the last two years. There have been many times that I’ve wanted to quit, but there have been almost as many times where I’ve loved it. Having a great experience with a table of strangers can be rewarding in and of itself and feels even better when you pocket a generous tip and a commendation for the great service.

This speaks to the exact kind of labor culture that William Scott is warning against. At the end of the day, I am basically working as a servant. I am bringing food and doing everything I can to ensure that the people I am taking care of are happy, including sacrificing my self-respect. Your server will do anything for you short of taking a bullet. They will apologize for things they have no control over and to people who are looking for something to complain about, they will watch you order meals they know they can’t afford and then be forced to throw out three-quarters of the sixty dollar steak you didn’t eat and “don’t want to take home”.

The drawbacks and benefits that ultimately inspired me to move into different sectors of food and service industry work were affected, first and foremost, by the amount of freedom they provided me as well as what kind of work I was doing (sound familiar?). I was willing to take on more labor intensive work for the assurance of better pay, but I was equally willing to sacrifice some of my financial security for a chance at a more leisurely work atmosphere and schedule. In order to “embrace the urban vitality” (Ross, 139), the lifestyle of ‘no collar’, I essentially left a more traditionally Fordist structured work-style for one based around the post-industrial labor principles that define much of the work of the “ new urban service industries” (Ross, 139) or, more broadly, the Creative Class.

Here is a particularly interesting podcast by Steve Levitt and Stephen Dubner, Freakonomics. (I couldn’t figure out how to embed the podcast)!

And here is a CollegeHumor video!

Leave a comment